- Justin Webb

Sunday 13 February 2011

- Article history

Very few American politicians could survive for long in British public life. It's not just the mental agility required for success in the House of Commons; it's the whole British culture of prodding and poking – the disrespect agenda of public and media – that would cause most of them to pass out or go back to making money quicker than you could say: "8.10 with John Humphrys."

-

Known and Unknown: A Memoir

- by

Donald Rumsfeld

-

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

Donald Rumsfeld is an exception. He had a disrespect agenda of his own. He got his retaliation in first. He would have mastered question time in the Commons and Question Time on the telly. In the British environment, he would occasionally have gone spectacularly off the rails – more Nicholas Fairbairn than Tony Blair – but he would have used his authenticity and his vicious tongue to good effect; this was a man who, in his pomp, was a political warrior without peer.

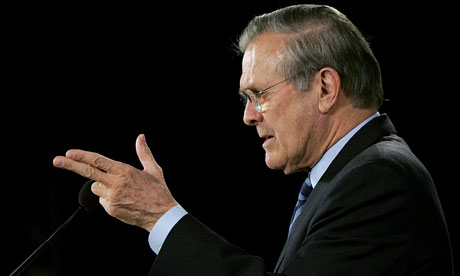

In my eight years in America for the BBC, I can honestly say that I never watched a single speech on the floor of either houses of Congress. But Rumsfeld's news conferences were a must-see. They were the nearest thing America had to prime minister's questions. Held in a bunker in the Pentagon, before an audience of nervous, tittering, chino-wearing, blue-shirted correspondents, these were spanking sessions for a generation of defence nerds.

Withering is the word that best describes his tone. He was sarcastic and gloating and sneering and personal and they loved it. Truth be told, some of them loved him. And if you think I am suggesting something vaguely erotic, well, I am.

My goodness me, as the man would say, eyes narrowing, former college wrestler's biceps tightening.

This book brings it all back. And before you ask why would that be a good thing, let me fill you in on what it felt like, in those days, to be American. It was hell. Folks led by a man who lived in a cave had just killed thousands of people, including more than 100 inside the Pentagon itself. There was still a hole in the wall. Above Washington, fighter planes rocketed around, desperate to shoot something down but succeeding only in further discomfiting the nation's capital.

And as if that wasn't bad enough, a couple of deranged snipers were picking off and killing people who were out shopping. Wars were being fought in Afghanistan and, very soon, Iraq. Young men were signing up for the army and Marines. America was, as the Americans say, in a bad place and wanted to fight its way out.

Cue Donald Rumsfeld. He was a known known in a world of unknown unknowns. His weird foray into the previously known unknown of metaphysical epistemology, much mocked by the British, suited perfectly the spooky tenor of the times.

So now, with the benefit of hindsight, is there anything he would like to withdraw? The answer comes in this book: nothing. Oh, the odd misspeak perhaps, but any hope among his enemies that he would take the tearful Robert McNamara route to salvation has been well and truly buried. Rumsfeld comes out fighting. Against Saddam, of course, but nor are other enemies forgotten.

A particularly delicious attack on the French comes in his recounting of his 1983 meeting with Saddam, during which the dictator said that France "understood the Iraqi view". Over the years that followed, Rumsfeld observes drily: "That particular remark came to my mind on more than one occasion and I never had cause to doubt it."

The biggest regret Rumsfeld has is that he failed to resign after the photographs of American soldiers abusing prisoners at Abu Ghraib came to light in 2004. He says he tried repeatedly to persuade President Bush to accept his resignation and Bush repeatedly refused. Eventually, Rumsfeld accepted that he should stay but, he writes: "This was a misjudgment on my part." Misjudgment? For a man so clear-eyed and strategy-driven, it seems an odd understatement.

His defence of Guantánamo, on the other hand, is compelling, at least as a counterweight to what in Britain has become a well-entrenched narrative that the prison was and is a disaster. The Rumsfeld case is that there was no alternative: "I was perfectly willing to shutter the facility if a better alternative could have been found that would be as effective in obtaining intelligence and preventing terrorists from returning to the fight. But no alternative to Gitmo was proposed." Of those wrongly imprisoned, there is no mention. Stuff happens, he seems to be saying.

Does the book tell us something about Rumsfeld that might serve to soften the verdict of history? There are glimpses of a man deeply attached to his wife, Joyce, to his family and friends, fighting the political fight in Washington but always connected to real human beings. His son, Nick, was addicted to drugs and just after 9/11 checked himself into a clinic. Rumsfeld describes a meeting with Bush in the Oval Office where they talk about Nick and, it seems, Rumsfeld breaks down:

"What had happened to Nick – coupled with the wounds to our country and the Pentagon – all started to hit me. At that moment, I couldn't speak. And I was unable to hold back the emotions that until then I had shared only with Joyce. I had not imagined I might choke up in a meeting with the president of the United States, but at that moment George W Bush wasn't just the president. He was a compassionate human being who had a sense of what Joyce and I were going through.

"Bush rose from his chair, walked around his desk, and put his arm around me."

I could have done with more of this and less of the grand strategy stuff, given that the strategy he pursued is now a known known.

Rumsfeld is without question one of the great figures of recent American politics. His career began in 1962 when, at the age of 30, he was first elected to Congress. He crossed swords with LBJ over Vietnam and worked for Nixon, whom he quotes dismissing his Nato staff as "a bunch of fairies". There are photos of Rumsfeld joshing with Kissinger, playing tennis with Ford, consulting with Reagan. He has been in the room – driven and focused and fascinating – during some of the most tumultuous moments of American history.

We needed more insight, more sense of detachment, for this book to match the achievements of its author. A mere reminder of why those press conferences were fun to watch is hardly enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment